| Toxoplasmosis | |

|---|---|

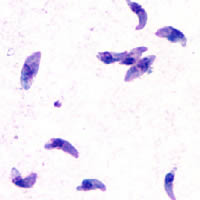

T. gondii tachyzoites

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | B58 |

| ICD-9-CM | 130 |

| DiseasesDB | 13208 |

| MedlinePlus | 000637 |

| eMedicine | med/2294 |

| Patient UK | Toxoplasmosis |

| MeSH | D014123 |

Up to half of the world's human population is estimated to carry a Toxoplasma infection.[3] The most recent U.S. data from 2014 indicated the rate as 22.5% nationwide and 29.2% in the northeast U.S.[4] One study claimed a seroprevalence of 75% in El Salvador.[5] Official assessment in Great Britain places the number of infections at about 350,000 a year.[6]

Toxoplasmosis is usually asymptomatic,[7][8] but during the first few weeks after exposure the infection may cause a mild, flu-like illness.[9] However, those with weakened immune systems, such as those with AIDS and pregnant women, may become seriously ill, and it can occasionally be fatal.[7] The parasite can cause encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), neurological diseases, and can affect the heart, liver, inner ears, and eyes (chorioretinitis).[10] Recent research has also linked toxoplasmosis with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and schizophrenia.[11] Numerous studies found a positive correlation between latent toxoplasmosis and suicidal behavior in humans.[12][13][14]

Charles Nicolle and Louis Manceaux first described the organism in 1908, after they observed the parasites in the blood, spleen, and liver of a North African rodent, Ctenodactylus gundi. The parasite was named Toxoplasma gondii, from the Greek words τόξον (toxon, "arc" or "bow") and πλάσμα (plasma, "creature"), and after the rodent, in 1909. In 1923, Janku reported parasitic cysts in the retina of an infant who had hydrocephalus, seizures, and unilateral microphthalmia. Wolf, Cowan, and Paige (1937–1939) determined these findings represented the syndrome of severe congenital T. gondii infection.[15]

Contents

[hide]Signs and symptoms[edit]

Infection has three stages:Acute toxoplasmosis[edit]

Acute toxoplasmosis is often asymptomatic in healthy adults.[7][8] However, symptoms may manifest and are often influenza-like: swollen lymph nodes, or muscle aches and pains that last for a month or more. Rarely will a human with a fully functioning immune system develop severe symptoms following infection. Young children and immunocompromised people, such as those with HIV/AIDS, those taking certain types of chemotherapy, or those who have recently received an organ transplant, may develop severe toxoplasmosis. This can cause damage to the brain (encephalitis) or the eyes (necrotizing retinochoroiditis).[16] Infants infected via placental transmission may be born with either of these problems, or with nasal malformations, although these complications are rare in newborns. The toxoplasmic trophozoites causing acute toxoplasmosis are referred to as Tachyzoites, and are typically found in bodily fluids.Swollen lymph nodes are commonly found in the neck or under the chin, followed by the armpits and the groin. Swelling may occur at different times after the initial infection, persist, and recur for various times independently of antiparasitic treatment.[17] It is usually found at single sites in adults, but in children, multiple sites may be more common. Enlarged lymph nodes will resolve within one to two months in 60% of cases. However, a quarter of those affected take two to four months to return to normal, and 8% take four to six months. A substantial number (6%) do not return to normal until much later.[18]

Latent toxoplasmosis[edit]

Due to its asymptomatic nature,[7][8] it is easy for a host to become infected with Toxoplasma gondii and develop toxoplasmosis without knowing it. In most immunocompetent people, the infection enters a latent phase, during which only bradyzoites are present,[19] forming cysts in nervous and muscle tissue. Most infants who are infected while in the womb have no symptoms at birth, but may develop symptoms later in life.[20]Cutaneous toxoplasmosis[edit]

While rare, skin lesions may occur in the acquired form of the disease, including roseola and erythema multiforme-like eruptions, prurigo-like nodules, urticaria, and maculopapular lesions. Newborns may have punctate macules, ecchymoses, or “blueberry muffin” lesions. Diagnosis of cutaneous toxoplasmosis is based on the tachyzoite form of T. gondii being found in the epidermis.[21] It is found in all levels of the epidermis, is about 6 μm by 2 μm and bow-shaped, with the nucleus being one-third of its size. It can be identified by electron microscopy or by Giemsa staining tissue where the cytoplasm shows blue, the nucleus red.[22]Cause[edit]

The parasite’s survival is dependent on a balance between host survival and parasite proliferation.[23] This is achieved through the reduction of host’s immune response and the enhancement of the parasite’s reproductive advantage, both of which occur through the parasite’s manipulation of the host’s immune response.[23] Once the parasite T. gondii infects a normal host cell, it resists damage caused by the host’s immune system, as well as changing the host's immune processes.In the host cell, the parasite is encapsulated in the parasitophorous vacuole (PV), whose membrane is a result of its forced entry into the cell.[9][24] The PV is both resistant to the activity of the endolysosomal system, and can take control of the host’s mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum.[9][24]

When first invading the cell, the parasite releases ROP proteins from the bulb of the rhoptry organelle.[9] These proteins translocate to the nucleus and the surface of the PV membrane where they can activate STAT pathways to modulate the expression of cytokines at the transcriptional level, bind and inactivate PV membrane destroying IRG proteins, among other possible effects.[9][24][25] Additionally, certain strains of T. gondii are capable of secreting another protein, known as GRA15 which can activate the NF-κB pathway, to upregulate the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12 in the early immune response, possibly leading to the parasite’s latent phase.[9] The parasite’s ability to secrete these proteins depends on its genotype and effects its virulence.[9][25]

The parasite also exerts an effect on an anti-apoptotic mechanism, allowing the infected host cells to persist and replicate. One method of apoptosis resistance is by disrupting pro-apoptosis effector proteins, such as Bax and Bak.[26] In order to disrupt these proteins, T. gondii causes conformational changes to the proteins.[26] These conformational changes result in the inability of the proteins to be transported to various cellular compartments and initiate apoptosis events. T. gondii does not, however, cause downregulation of the pro-apoptosis effector proteins.[26]

T. gondii also has the ability to initiate autophagy of the host’s cells.[27] This leads to a decrease in healthy, uninfected cells, and consequently less host cells to attack the infected cells. Research by Wang et al finds that infected cells lead to higher levels of autophagosomes in normal and infected cells.[27] Their research reveals that T. gondii causes host cell autophagy using a calcium-dependent pathway.[27] Another study suggests that the parasite can directly affect calcium being released from calcium stores, which are important for the signalling processes of cells.[26]

The mechanisms above are very important ways in which T. gondii is able to persist in a host causing many serious problems for the host. Some limiting factors for the plasmid is that its effects on the host cells seem to thrive in a weak immune system and be dosage dependent, so a large number of T. gondii must be present per host cell to have a more severe effect.[28] The effect on the host also relies on the host having a weakened immune system. Immunocompetent individuals do not normally show severe symptoms or any at all, while fatality or severe complications can result in immunocompromised individuals.[28]

It should be noted that since the parasite can change the host’s immune response, it may also have an effect, positive or negative, on the immune response to other pathogenic threats.[23] This includes, but is not limited to, the responses to infections by Helicobacter felis, Leishmania major, or other parasites, such as Nippostrongylus brasiliensis.[23]

Transmission[edit]

Transmission may occur through:- Ingestion of raw or partly cooked meat, especially pork, lamb, or venison containing Toxoplasma cysts: Infection prevalence in countries where undercooked meat is traditionally eaten has been related to this transmission method. Tissue cysts may also be ingested during hand-to-mouth contact after handling undercooked meat, or from using knives, utensils, or cutting boards contaminated by raw meat.[29]

- Ingestion of unwashed fruits or vegetables that have been in contact with contaminated soil containing infected cat feces.[30]

- Ingestion of contaminated cat feces: This can occur through hand-to-mouth contact following gardening, cleaning a cat's litter box, contact with children's sandpits; the parasite can survive in the environment for over a year.[31]

- Acquiring congenital infection through the placenta.[16]

Pregnancy precautions[edit]

Congenital toxoplasmosis is a special form in which an unborn fetus is infected via the placenta.[33] A positive antibody titer indicates previous exposure and immunity, and largely ensures the unborn fetus' safety. A simple blood draw at the first prenatal doctor visit can determine whether or not a woman has had previous exposure and therefore whether or not she is at risk. If a woman receives her first exposure to T. gondii while pregnant, the fetus is at particular risk.Pregnant women should avoid handling raw meat, drinking raw milk (especially goat milk) and be advised to not eat raw or undercooked meat regardless of type.[34] Because of the obvious relationship between Toxoplasma and cats it is also often advised to avoid exposure to cat feces, and refrain from gardening (cat feces are common in garden soil) or at least wear gloves when so engaged.[34] Most cats are not actively shedding oocysts since they get infected in the first 6 months of their life. They shed oocysts for only a short period of time (1–2 weeks.)[35] However, these oocysts get buried in the soil, sporulate and remain infectious for periods ranging from several months to more than a year.[34] Numerous studies have shown living in a household with a cat is not a significant risk factor for T. gondii infection,[34][36][37] though living with several kittens has some significance.[38]

For pregnant women with negative antibody titers, indicating no previous exposure to T. gondii, serology testing as frequent as monthly is advisable as treatment during pregnancy for those women exposed to T. gondii for the first time decreases dramatically the risk of passing the parasite to the fetus.

Despite these risks, pregnant women are not routinely screened for toxoplasmosis in most countries (Portugal,[39] France,[40] Austria,[40] Uruguay,[41] and Italy[42] being the exceptions) for reasons of cost-effectiveness and the high number of false positives generated. As invasive prenatal testing incurs some risk to the fetus (18.5 pregnancy losses per toxoplasmosis case prevented),[40] postnatal or neonatal screening is preferred. The exceptions are cases where fetal abnormalities are noted, and thus screening can be targeted.[40]

Some regional screening programmes operate in Germany, Switzerland and Belgium.[42]

Treatment is very important for recently infected pregnant women, to prevent infection of the fetus. Since a baby's immune system does not develop fully for the first year of life, and the resilient cysts that form throughout the body are very difficult to eradicate with antiprotozoans, an infection can be very serious in the young.

In 2006, a Czech research team[43] discovered women with high levels of toxoplasmosis antibodies were significantly more likely to have baby boys than baby girls. In most populations, the birth rate is around 51% boys, but women infected with T. gondii had up to a 72% chance of a boy.[44][45] In mice, the sex ratio was higher in early latent toxoplasmosis and lower in later latent toxoplasmosis.[45]

Rodent behavior[edit]

Infection with T. gondii has been shown to alter the behavior of mice and rats in ways thought to increase the rodents’ chances of being preyed upon by cats.[46][47][48] Infected rodents show a reduction in their innate aversion to cat odors; while uninfected mice and rats will generally avoid areas marked with cat urine or with cat body odor, this avoidance is reduced or eliminated in infected animals.[46][48][49] Moreover, some evidence suggests this loss of aversion may be specific to feline odors: when given a choice between two predator odors (cat or mink), infected rodents show a significantly stronger preference to cat odors than do uninfected controls.[50][51]In rodents, T. gondii–induced behavioral changes occur through epigenetic remodeling in neurons associated observed behaviors;[52][53] for example, it modifies epigenetic methylation to induce hypomethylation of arginine vasopressin-related genes in the medial amygdala to greatly decrease predator aversion.[52][53] Similar epigenetically-induced behavioral changes have also been observed in mouse models of addiction, where changes in the expression of histone-modifying enzymes via gene knockout or enzyme inhibition in specific neurons produced alterations in drug-related behaviors.[54][55][56] Widespread histone-lysine acetylation in cortical astrocytes appears to be another epigenetic mechanism employed by T. gondii.[57][58]

T. gondii-infected rodents show a number of behavioral changes beyond altered responses to cat odors. Rats infected with the parasite show increased levels of activity and decreased neophobic behavior.[47][59] Similarly, infected mice show alterations in patterns of locomotion and exploratory behavior during experimental tests. These patterns include traveling greater distances, moving at higher speeds, accelerating for longer periods of time, and showing a decreased pause-time when placed in new arenas.[60] Infected rodents have also been shown to have differences in traditional measures of anxiety, such as elevated plus mazes, open field arenas, and social interaction tests.[60][61]

Diagnosis[edit]

Diagnosis of toxoplasmosis in humans is made by biological, serological, histological, or molecular methods, or by some combination of the above.[35] Toxoplasmosis can be difficult to distinguish from primary central nervous system lymphoma. It mimics several other infectious diseases so clinical signs are non-specific and are not sufficiently characteristic for a definite diagnosis. As a result, the diagnosis is made by a trial of therapy (pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid (USAN: leucovorin)), followed by a brain biopsy if the drugs produce no effect clinically and no improvement on repeat imaging.Detection of T. gondii in human blood samples may also be achieved by using the polymerase chain reaction.[62] Inactive cysts may exist in a host that would evade detection.

Several serological procedures are available for the detection of T. gondii antibody in patients, which may aid diagnosis; these include the Sabin–Feldman dye test (DT), the indirect hemagglutination assay, the indirect fluorescent antibody assay (IFA), the direct agglutination test, the latex agglutination test (LAT), the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and the immunosorbent agglutination assay test (IAAT). The IFA, IAAT and ELISA have been modified to detect immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies.[35]

- IgG antibody

Acute infections can be differentiated from chronic infections using the “differential” agglutination test (also known as the AC/HS test), which is best used in combination with a panel of other tests such as the TSP.[63] The AC/HS test results when parasites are fixed for use in the agglutination test with two different compounds (i.e., acetone and formalin). The different antigenic preparations vary in their ability to recognize sera obtained during the acute and chronic stages of the infection.[63]

- IgM antibody

- Congenital toxoplasmosis

Even though diagnosis of toxoplasmosis heavily relies on serological detection of specific anti-Toxoplasma immunoglobulin, serological testing does have its limitations. For example, it may fail to detect the active phase of T. gondii infection because the specific anti-Toxoplasma IgG or IgM may not be produced until after several weeks of parasitemia. As a result, a pregnant mother might test negative during the active phase of T. gondii infection leading to the undetection of congenital toxoplasmosis of a fetus.[65] Also, the test may fail to detect T. gondii infections in immunocompromised patients because the titers of specific anti-Toxoplasma IgG or IgM may fail to rise in this type of patient.

A lot of PCR-based techniques have been developed for the diagnosis of toxoplasmosis using various clinical specimens, including amniotic fluid, blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and tissue biopsy. The most sensitive method among the PCR-based techniques is nested PCR followed by hybridization of PCR products.[65] The major downside to these techniques is that they are time consuming and do not provide quantitative data.[65]

Real-time PCR is useful in pathogen detection, gene expression and regulation, and allelic discrimination. This PCR technique utilizes the 5' nuclease activity of Taq DNA polymerase to cleave a nonextendible, fluorescence-labeled hybridization probe during the extension phase of PCR.[65] A second fluorescent dye, e.g., 6-carboxy-tetramethyl-rhodamine, quenches the fluorescence of the intact probe.[65] The nuclease cleavage of the hybridization probe during the PCR releases the effect of quenching resulting in an increase of fluorescence proportional to the amount of PCR product, which can be monitored by a sequence detector.[65]

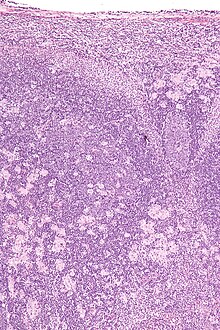

Toxoplasmosis cannot be detected with immunostaining. Lymph nodes affected by Toxoplasma have characteristic changes, including poorly demarcated reactivegerminal centers, clusters of monocytoid B cells, and scattered epithelioid histiocytes.

Treatment[edit]

Treatment is often only recommended for people with serious health problems, such as people with HIV whose CD4 counts are under 200, because the disease is most serious when one's immune system is weak. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is the drug of choice to prevent toxoplasmosis, but not for treating active disease. A new study (May 2012) shows a promising new way to treat the active and latent form of this disease using two endochin-like quinolones.[66]Acute[edit]

The medications prescribed for acute toxoplasmosis are the following:- Pyrimethamine — an antimalarial medication

- Sulfadiazine — an antibiotic used in combination with pyrimethamine to treat toxoplasmosis

- Combination therapy is usually given with folic acid supplements to reduce incidence of thrombocytopaenia.

- Combination therapy is most useful in the setting of HIV.

- Clindamycin

- Spiramycin — an antibiotic used most often for pregnant women to prevent the infection of their children

Latent[edit]

In people with latent toxoplasmosis, the cysts are immune to these treatments, as the antibiotics do not reach the bradyzoites in sufficient concentration.The medications prescribed for latent toxoplasmosis are:

- Atovaquone — an antibiotic that has been used to kill Toxoplasma cysts inside AIDS patients[67]

- Clindamycin — an antibiotic that, in combination with atovaquone, seemed to optimally kill cysts in mice[68]

Epidemiology[edit]

T. gondii infections occur throughout the world, although infection rates differ significantly by country.[69] For women of childbearing age, a survey of 99 studies within 44 countries found the areas of highest prevalence are within Latin America (about 50–80%), parts of Eastern and Central Europe (about 20–60%), the Middle East (about 30-50%), parts of Southeast Asia (about 20–60%), and parts of Africa (about 20–55%).[69]In the United States, data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2004 found 9.0% of US-born persons 12–49 years of age were seropositive for IgG antibodies against T. gondii, down from 14.1% as measured in the NHANES 1988–1994.[70] In the 1999–2004 survey, 7.7% of US-born and 28.1% of foreign-born women 15–44 years of age were T. gondii seropositive.[70] A trend of decreasing seroprevalence has been observed by numerous studies in the United States and many European countries.[69]

The protist responsible for Toxoplasmosis is T. gondii. There are three major types of T. gondii responsible for the patterns of Toxoplasmosis throughout the world. There is type I, II, and III. These three types of T. gondii have differing effects on certain hosts, mainly mice and humans due to their variation in genotypes.[45]

- Type I: virulent in mice and humans, seen in AIDS patients.

- Type II: non-virulent in mice, virulent in humans (mostly Europe and North America), seen in AIDS patients.

- Type III: non-virulent in mice, virulent mainly in animals but seen to a lesser degree in humans as well.

Because the parasite poses a particular threat to fetuses when it is contracted during pregnancy,[72] much of the global epidemiological data regarding T. gondii comes from seropositivity tests in women of childbearing age. Seropositivity tests look for the presence of antibodies against T. gondii in blood, so while seropositivity guarantees one has been exposed to the parasite, it does not necessarily guarantee one is chronically infected.[73]

History[edit]

Toxoplasma gondii was first described in 1908 by Nicolle and Manceaux in Tunisia, and independently by Splendore in Brazil.[74] Splendore reported the protozoan in a rabbit, while Nicolle and Manceaux identified it in a North African rodent, the gundi (Ctenodactylus gundi).[75] In 1909 Nicolle and Manceaux differentiated the protozoan from Leishmania.[74] Nicolle and Manceaux then named it Toxoplasma gondii after the curved shape of its infectious stage (Greek root ‘toxon’= bow).[74]The first recorded case of congenital toxoplasmosis was in 1923, but it was not identified as caused by T. gondii.[75] Janků (1923) described in detail the autopsy results of an 11-month-old boy who had presented to hospital with hydrocephalus. The boy had classic marks of toxoplasmosis including chorioretinitis (inflammation of the choroid and retina of the eye).[75] Histology revealed a number of “sporocytes”, though Janků did not identify these as T. gondii.[75]

It was not until 1937 that the first detailed scientific analysis of T. gondii took place using techniques previously developed for analyzing viruses.[74] In 1937 Sabin and Olitsky analyzed T. gondii in laboratory monkeys and mice. Sabin and Olitsky showed that T. gondii was an obligate intracellular parasite and that mice fed T. gondii-contaminated tissue also contracted the infection.[74] Thus Sabin and Olitsky demonstrated T. gondii as a pathogen transmissible between animals.

T. gondii was first identified as a human pathogen in 1939.[74] Wolf, Cowen and Paige identified T. gondii infection in an infant girl delivered full-term by Caesarean section.[75] The infant developed seizures and had chorioretinitis in both eyes at three days. The infant then developed encephalomyelitis and died at one month of age. Wolf, Cowen and Paige isolated T. gondii from brain tissue lesions. Intracranial injection of brain and spinal cord samples into mice, rabbits and rats produced encephalitis in the animals.[74] Wolf, Cowen and Page reviewed additional cases and concluded that T. gondii produced recognizable symptoms and could be transmitted from mother to child.[75]

The first adult case of toxoplasmosis was reported in 1940 with no neurological signs. Pinkerton and Weinman reported the presence of Toxoplasma in a 22-year-old man from Peru who died from a subsequent bacterial infection and fever.[75]

In 1948, a serological dye test was created by Sabin and Feldman based on the ability of the patient’s antibodies to alter staining of Toxoplasma.[74][76] The Sabin Feldman Dye Test is now the gold standard for identifying Toxoplasma infection.[74]

Transmission of Toxoplasma by eating raw or undercooked meat was demonstrated by Desmonts et al. in 1965 Paris.[74] Desmonts observed that the therapeutic consumption of raw beef or horse meat in a tuberculosis hospital was associated with a 50% per year increase in Toxoplasma antibodies.[74] This means that more T. gondii was being transmitted through the raw meat.

In 1974, Desmonts and Couvreur showed that infection during the first two trimesters produces most harm to the fetus, that transmission depended on when mothers were infected during pregnancy, that mothers with antibodies before pregnancy did not transmit the infection to the fetus, and that spiramycin lowered the transmission to the fetus.[75]

Toxoplasma gained more attention in the 1970s with the rise of immune-suppressant treatment given after organ or bone marrow transplants and the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s.[74] Patients with lowered immune system function are much more susceptible to disease.

Society and culture[edit]

"Crazy cat lady syndrome"[edit]

"Crazy cat lady syndrome" is a term coined by news organizations to describe scientific findings that link the parasite Toxoplasma gondii to several mental disorders and behavioral problems.[77][78][79][80][81] Although researches found that cat ownership does not strongly increase the risk of T. gondii infection on pregnant women,[82][83] the strong correlation between the cat ownership on childhood and later development of schizophrenia suggests it is indeed a risk factor for children.[84] The term crazy cat lady syndrome draws on both stereotype and popular cultural reference. It was originated as instances of the aforementioned afflictions were noted amongst the populace. Cat lady is a cultural stereotype of a woman who compulsively hoards cats and dotes upon them, often a spinster. Jaroslav Flegr (biologist) is a proponent of the theory that toxoplasmosis affects human behavior.[85][86]Notable cases[edit]

- Arthur Ashe (tennis player) developed neurological problems from toxoplasmosis (and was later found to be HIV-positive).[87]

- Merritt Butrick (actor) was HIV-positive and died from toxoplasmosis as a result of his already-weakened immune system.[88]

- Prince François, Count of Clermont (pretender to the throne of France); his disability caused him to be overlooked in the line of succession.

- Leslie Ash (actress) contracted toxoplasmosis in the second month of pregnancy.[89]

- Sebastian Coe (British middle-distance runner)[90]

- Martina Navratilova suffered from toxoplasmosis during the 1982 US Open.[91]

- Louis Wain (artist) was famous for painting cats; he later developed schizophrenia, which some believe was due to toxoplasmosis resulting from his prolonged exposure to cats.[92]

- The Wealdstone Raider suffered toxoplasmosis for much of his childhood and adolescence.[93]

In popular culture[edit]

- In The Fallen (2013), book five of Charlie Higson's post-apocalyptic series The Enemy, Skinman explains to Blue that the "Nightmare Bug" that's afflicted the adults and deformed the children of the scientists who originally contracted it is akin to toxoplasmosis.[94] This explanation recalls Maxie's story about her despondent friend Lila's having become suicidal following the deaths of her cat and kitten, who were suffering from cat flu,[95] and it implies possible contributions to the transformations of such characters as Paul, who had been mourning his sister's death and whose personality changed when he began exhibiting flu-like symptoms,[96] after being bitten by a diseased adult;[97] and the undue risk-taking by such characters as Jake[98] (who like the other children, had lost friends and family and had to fight and kill to survive). Skinman's explanation also recalls cat-lover Frederique Morel (first encountered in The Dead (2010)), who remained despondent after her father's death and eventually transformed[99] while some others who reached her age (e.g., Blue[100]) did not.

- In 1993 novel Trainspotting, character Matty dies of toxoplasmosis exacerbated by AIDS. For the film, the character who dies of toxoplasmosis is instead Tommy.

Other animals[edit]

T. gondii infects virtually all warm-blooded animals; these tachyzoites were found in a bird[101]

Although infection with T. gondii has been noted in several species of Asian primates, seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies was found for the first time in toque macaques (Macaca sinica) that are endemic to the island of Sri Lanka.[103]

Livestock[edit]

Among livestock, pigs, sheep[104] and goats have the highest rates of chronic T. gondii infection.[105] The prevalence of T. gondii in meat-producing animals varies widely both within and between countries,[105] and rates of infection have been shown to be dramatically influenced by varying farming and management practices.[8] For instance, animals kept outdoors or in free-ranging environments are more at risk of infection than animals raised indoors or in commercial confinement operations.[8][106]In the United States, the percentage of pigs harboring viable parasites has been measured (via bioassay in mice or cats) to be as high as 92.7% and as low as 0%, depending on the farm or herd.[106] Surveys of seroprevalence (T. gondii antibodies in blood) are more common, and such measurements are indicative of the high relative seroprevalence in pigs across the world.[107] Along with pigs, sheep and goats are among the most commonly infected livestock of epidemiological significance for human infection.[105] Prevalence of viable T. gondii in sheep tissue has been measured (via bioassay) to be as high as 78% in the United States,[108] and a 2011 survey of goats intended for consumption in the United States found a seroprevalence of 53.4%.[109]

Due to a lack of exposure to the outdoors, chickens raised in large-scale indoor confinement operations are not commonly infected with T. gondii.[8] Free-ranging or backyard-raised chickens are much more commonly infected.[8] A survey of free-ranging chickens in the United States found its prevalence to be 17%–100%, depending on the farm.[110] Because chicken meat is generally cooked thoroughly before consumption, poultry is not generally considered to be a significant risk factor for human T. gondii infection.[111]

Although cattle and buffalo can be infected with T. gondii, the parasite is generally eliminated or reduced to undetectable levels within a few weeks following exposure.[8] Tissue cysts are rarely present in buffalo meat or beef, and meat from these animals is considered to be low-risk for harboring viable parasites.[105][106]

Horses are considered resistant to chronic T. gondii infection.[8] However, viable cells have been isolated from US horses slaughtered for export, and severe human toxoplasmosis in France has been epidemiologically linked to the consumption of horse meat.[106]

Domestic cats[edit]

The seroprevalence of T. gondii in domestic cats, worldwide, has been estimated to be around 30–40%.[112] In the United States, no official national estimate has been made, but local surveys have shown levels varied between 16% and 80%.[112] A 2012 survey of 445 purebred pet cats and 45 shelter cats in Finland found an overall seroprevalence of 48.4%.[113] A 2010 survey of feral cats from Giza, Egypt, found an overall seroprevalence of 97.4%.[114]T. gondii infection rates in domestic cats vary widely depending on the cats' diets and lifestyles.[115] Feral cats that hunt for their food are more likely to be infected than domestic cats. The prevalence of T. gondii in cat populations depends on the availability of infected birds and small mammals,[116] but often this prey is abundant.

Most infected cats will shed oocysts only once in their lifetimes, for a period of about one to two weeks.[112] Although this period of shedding is quite transient, millions of oocysts can be shed, with each oocyst capable of spreading and surviving for months.[112] An estimated 1% of cats at any given time are actively shedding oocysts.[8]

Marine mammals[edit]

A University of California, Davis study of dead sea otters collected from 1998 to 2004 found toxoplasmosis was the cause of death for 13% of the animals.[117] Proximity to freshwater outflows into the ocean was a major risk factor. Ingestion of oocysts from cat feces is considered to be the most likely ultimate source.[118] Surface runoff containing wild cat feces and litter from domestic cats flushed down toilets are possible sources of oocysts.[119] The parasites have been found in dolphins and whales.[120] Researchers Black and Massie believe anchovies, which travel from estuaries into the open ocean, may be helping to spread the disease.Research[edit]

Chronic infection with T. gondii has traditionally been considered asymptomatic in immunocompetent human hosts. However, accumulating evidence suggests latent infection may subtly influence a range of human behaviors and tendencies, and infection may alter the susceptibility to or intensity of a number of affective, psychiatric, or neurological disorders.[121]

Micrograph of a lymph node showing the characteristic changes of toxoplasmosis (scattered epithelioid histiocytes (pale cells), monocytoid cells (top-center of image), large germinal centers (left of image)) H&E stain

Schizophrenia[edit]

The most substantial body of evidence linking T. gondii to a neurological disorder involves the potential association between schizophrenia and infection with the parasite.[46][123] A 2007 meta-analysis, including 23 studies, found the prevalence of antibodies to T.gondii in schizophrenia patients was significantly higher than that in control populations, with a combined odds ratio of 2.73 (95% CI 2.10-3.60). These results suggest individuals with schizophrenia have an increased prevalence of antibodies to T.gondii compared to the general population.[123] Furthermore, this odds ratio suggests a stronger association between schizophrenia and T.gondii antibodies than any human gene identified in schizophrenia genome-wide association studies (OR from 1.6-1.8)[123][124] In 2012, an updated meta-analysis included 15 additional studies, for a total of 38 studies that together show a positive correlation between T.gondii antibody titres and schizophrenia with a reconfirmed combined odds ratio of 2.73 (95% CI 2.21-3.28).[125] T.gondii antibody positivity was therefore considered an intermediate risk factor in relation to other known schizophrenia risk factors.[125]While the vast majority of these studies tested people already diagnosed with schizophrenia for T. gondii antibodies, significant associations between T. gondii and schizophrenia have been found prior to the onset of schizophrenia disease symptoms.[46] For example, a study of 180 military personnel who were demilitarized due to a schizophrenia diagnosis found significantly increased levels of T.gondii antibodies detected in frozen blood samples collected prior to their schizophrenia diagnosis.[126] Additionally, among the 23 studies included in the 2007 meta-analysis, seven investigated T.gondii antibody levels associated with first-episode schizophrenia for which the combined odds ratio was 2.54, which was not significantly different than the odds ratio for studies including all schizophrenia patients (OR=2.79).[123]

In order to explain the observed correlation between toxoplasmosis and schizophrenia, studies have been conducted in search for evidence of a causal role for T.gondii in triggering schizophrenia. One study used voxel-based morphometry to measure grey matter volume of brain areas in patients with schizophrenia.[127] Whereas previous studies have determined that patients with schizophrenia have reduced overall grey matter volume in select brain areas compared to healthy controls, the above-mentioned study determined that grey matter reductions were significantly greater in T.gondii seropositive schizophrenia patients compared to T.gondii seronegative schizophrenia patients. Additionally, grey matter volume did not differ significantly in relation to T.gondii status in patients without schizophrenia.[127] Furthermore, one study compared differences in schizophrenia onset and severity between toxoplasmosis-infected and toxoplasmosis-free patients and found toxoplasmosis-infected schizophrenia patients show more severe psychosis symptoms compared to toxoplasmosis-free patients.[128] This same study found that while the average onset of schizophrenia is approximately equal for toxoplasmosis seronegative males and females, the average onset of schizophrenia was approximately 3 years later in toxoplasmosis-infected females compared to males.[128] Studies attempting to explain this sex-dependent disparity in schizophrenia onset have suggested it can be accounted for by a previously characterized second peak of T.gondii infection incidence occurring from ages 25–30 observed in females only.[129][130] Additionally, patients with schizophrenia and T. gondii antibodies show a higher mortality rate than schizophrenics testing seronegative.[45] Also, minocycline, an antibiotic capable of passing the blood-brain barrier used for treating toxoplasmosis, has been found to help the symptoms of schizophrenia.[131]

Although a physiological mechanism supporting the association between schizophrenia and T.gondii infection is largely unknown, studies have attempted to discern a molecular mechanism to explain the correlation.[130] A T.gondii genome sequencing study found two genes encoding for an enzyme with significant homology to mammalian tyrosine hydroxylase, an enzyme involved in the conversion of tyrosine to the known dopamine precursor, L-DOPA [132] Schizophrenia has long been linked to dopamine dysregulation.[133] Therefore, this parasite-synthesized enzyme may contribute to the behavioral changes observed in toxoplasmosis by altering the production of dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in mood, sociability, attention, motivation, and sleep patterns. Animal studies have shown significant tyrosine hydroxylase activity and increased dopamine levels within T.gondii cysts.[134] Additionally, studies have suggested that interferon gamma (IFNγ ), secreted in response to T. gondii infection, induces astrocytes to produce indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO).[135] Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is a rate-limiting enzyme involved in a pathway that catabolizes tryptophan to kynurenic acid (KYNA), which is a known antagonist of glutamate NMDA receptors thought to play an important role in schizophrenia.[136]

Traffic accidents[edit]

In addition to a correlation with psychological disorders such as OCD, schizophrenia, and depression, T. gondii can also lead to infected people having a higher risk of being in a car accident than uninfected individuals.[45] A study in the Czech Republic found that latent toxoplasmosis patients were involved in accidents 2.65 times more often than people without toxoplasmosis infection.[45] The risk also increased with significantly higher amounts of T. gondii antibodies in the host cells.[45]Limitations of correlation analysis[edit]

In most of the current studies where positive correlations have been found between T. gondii antibody titers and certain behavioral traits or neurological disorders, T. gondii seropositivity tests are conducted after the onset of the examined disease or behavioral trait; that is, it is often unclear whether infection with the parasite increases the chances of having a certain trait or disorder, or if having a certain trait or disorder increases the chances of becoming infected with the parasite.[137] Groups of individuals with certain behavioral traits or neurological disorders may share certain behavioral tendencies that increase the likelihood of exposure to and infection with T. gondii; as a result, it is difficult to confirm causal relationships between T. gondii infections and associated neurological disorders or behavioral traits.[137] Provided there is in fact an etiological link between T. gondii and schizophrenia, studies have yet to determine why some individuals with latent toxoplasmosis develop schizophrenia while others do not, however, some plausible explanations include differing genetic susceptibility, parasite strain differences, and differences in the route of the acquired T.gondii infection.[123]See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Jump up ^ Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 723–7. ISBN 0838585299.

- Jump up ^ Dubey, J. P., et al. "Prevalence of Viable Toxoplasma Gondii in Beef, Chicken, and Pork from Retail Meat Stores in the United States: Risk Assessment to Consumers." The Journal of Parasitology Vol. 91.5 (2005): 1082-093. JSTOR. The American Society of Parasitologists. Web. 1 Dec. 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20059823.

- Jump up ^ Flegr J, Prandota J, Sovičková M, Israili ZH (March 2014). "Toxoplasmosis--a global threat. Correlation of latent toxoplasmosis with specific disease burden in a set of 88 countries". PLoS ONE 9 (3): e90203. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090203. PMC 3963851. PMID 24662942.

Toxoplasmosis is becoming a global health hazard as it infects 30-50% of the world human population. Clinically, the life-long presence of the parasite in tissues of a majority of infected individuals is usually considered asymptomatic. However, a number of studies show that this 'asymptomatic infection' may also lead to development of other human pathologies. ... The seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis correlated with various disease burden. Statistical associations does not necessarily mean causality. The precautionary principle suggests however that possible role of toxoplasmosis as a triggering factor responsible for development of several clinical entities deserves much more attention and financial support both in everyday medical practice and future clinical research.

- Jump up ^ Jones JL, Parise ME, Fiore AE (2014). "Neglected parasitic infections in the United States: toxoplasmosis". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 90 (5): 794–9. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0722. PMC 4015566. PMID 24808246.

- Jump up ^ Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O (2004). "Toxoplasmosis". Lancet 363 (9425): 1965–76. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X. PMID 15194258.

- Jump up ^ Connor, Steve (2012-09-04). "Beware of the cat: Britain's hidden toxoplasma problem". The Independent (London).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Dupont CD, Christian DA, Hunter CA (2012). "Immune response and immunopathology during toxoplasmosis". Seminars in Immunopathology 34 (6): 793–813. doi:10.1007/s00281-012-0339-3. PMC 3498595. PMID 22955326.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Dubey JP, Jones JL (September 2008). "Toxoplasma gondii infection in humans and animals in the United States". International Journal for Parasitology 38 (11): 1257–78. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.03.007. PMID 18508057.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Hunter, CA; Sibley, LD (November 2012). "Modulation of innate immunity by Toxoplasma gondii virulence effectors". Nature Reviews Microbiology 10 (11): 766–78. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2858. PMID 23070557.

- Jump up ^ Bin Dajem SM, Almushait MA (2012). "Detection of Toxoplasma gondii DNA by PCR in blood samples collected from pregnant Saudi women from the Aseer region, Saudi Arabia". Annals of Saudi Medicine 32 (5): 507–12. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2012.14.7.1200. PMID 22796740.

- Jump up ^ How Your Cat Is Making You Crazy

- Jump up ^ Zhang Y, Träskman-Bendz L, Janelidze S, Langenberg P, Saleh A, Constantine N, Okusaga O, Bay-Richter C, Brundin L, Postolache TT (Aug 2012). "Toxoplasma gondii immunoglobulin G antibodies and nonfatal suicidal self-directed violence". J Clin Psychiatry 73 (8): 1069–76. doi:10.4088/JCP.11m07532. PMID 22938818.

- Jump up ^ Pedersen MG, Mortensen PB, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Postolache TT (2012). "Toxoplasma gondii infection and self-directed violence in mothers". Archives of General Psychiatry 69 (11): 1123–30. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.668. PMID 22752117.

- Jump up ^ Ling VJ, Lester D, Mortensen PB, Langenberg PW, Postolache TT (2011). "Toxoplasma gondii Seropositivity and Suicide rates in Women". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 199 (7): 440–444. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e318221416e. PMC 3128543. PMID 21716055.

- Jump up ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jones JL, Kruszon-Moran D, Wilson M, McQuillan G, Navin T, McAuley JB (2001). "Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States: seroprevalence and risk factors". American Journal of Epidemiology 154 (4): 357–65. doi:10.1093/aje/154.4.357. PMID 11495859.

- Jump up ^ Paul M (1 July 1999). "Immunoglobulin G Avidity in Diagnosis of Toxoplasmic Lymphadenopathy and Ocular Toxoplasmosis". Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6 (4): 514–8. PMC 95718. PMID 10391853.

- Jump up ^ "Lymphadenopathy". Btinternet.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2010-07-28.[dead link]

- Jump up ^ Dubey JP, Hodgin EC, Hamir AN (2006). "Acute fatal toxoplasmosis in squirrels (Sciurus carolensis) with bradyzoites in visceral tissues". The Journal of Parasitology 92 (3): 658–9. doi:10.1645/GE-749R.1. PMID 16884019.

- Jump up ^ Randall Parker: Humans Get Personality Altering Infections From Cats. September 30, 2003

- Jump up ^ Barakat AM, Salem LM, El-Newishy AM, Shaapan RM, El-Mahllawy EK (2012). "Zoonotic chicken toxoplasmosis in some Egyptians governorates". Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences: PJBS 15 (17): 821–6. doi:10.3923/pjbs.2012.821.826. PMID 24163965.

- Jump up ^ Klaus, Sidney N.; Shoshana Frankenburg, and A. Damian Dhar (2003). "Chapter 235: Leishmaniasis and Other Protozoan Infections". In Freedberg et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138067-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Miller CM; Boulter NR; Ikin RJ; Smith NC (January 2009). "The immunobiology of the innate response to Toxoplasma gondii". International Journal for Parasitology 39 (1): 23–39. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.08.00. PMID 18775432.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Martens S; Parvanova I; Zerrahn J; Griffiths G; Schell G; Reichmann G; Howard JC (November 2005). "Disruption of Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuoles by the mouse p47-resistance GTPases". PLoS Pathogens 1 (3): e24. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0010024. PMID 16304607.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Denkers, EY; Schneider, AG; Cohen, AB; Butcher, BA (2012). "Phagocyte responses to protozoan infection and how Toxoplasma gondii meets the challenge". PLoS Pathogens 8 (8): e1002794. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002794. PMID 22876173.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hippe D, Weber A, Zhou L, Chang DC, Häcker G, Lüder CG (2009). "Toxoplasma gondii infection confers resistance against BimS-induced apoptosis by preventing the activation and mitochondrial targeting of pro-apoptotic Bax". Journal of Cell Science 122 (Pt 19): 3511–21. doi:10.1242/jcs.050963. PMID 19737817.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wang Y, Weiss LM, Orlofsky A (2009). "Host cell autophagy is induced by Toxoplasma gondii and contributes to parasite growth". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 284 (3): 1694–701. doi:10.1074/jbc.M807890200. PMC 2615531. PMID 19028680.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Laliberté J, Carruthers VB (2008). "Host cell manipulation by the human pathogen Toxoplasma gondii". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences : CMLS 65 (12): 1900–15. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-7556-x. PMC 2662853. PMID 18327664.

- Jump up ^ "Toxoplasmosis". Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. 2004-11-22.

- Jump up ^ Jones JL, Dubey JP (2012). "Foodborne toxoplasmosis". Clinical Infectious Diseases : an Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 55 (6): 845–51. doi:10.1093/cid/cis508. PMID 22618566.

- Jump up ^ North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services

- Jump up ^ "Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection)". Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. 2011-04-05.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sterkers Y, Ribot J, Albaba S, Issert E, Bastien P, Pratlong F (2011). "Diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis by polymerase chain reaction on neonatal peripheral blood". Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 71 (2): 174–6. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.06.006. PMID 21856107.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kapperud G, Jenum PA, Stray-Pedersen B, Melby KK, Eskild A, Eng J (1996). "Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in pregnancy. Results of a prospective case-control study in Norway". American Journal of Epidemiology 144 (4): 405–12. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008942. PMID 8712198.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hill D, Dubey JP (2002). "Toxoplasma gondii: transmission, diagnosis and prevention". Clinical Microbiology and Infection : the Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 8 (10): 634–40. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0691.2002.00485.x. PMID 12390281.

- Jump up ^ Cook AJ, Gilbert RE, Buffolano W, Zufferey J, Petersen E, Jenum PA, Foulon W, Semprini AE, Dunn DT (Jul 15, 2000). "Sources of toxoplasma infection in pregnant women: European multicentre case-control study. European Research Network on Congenital Toxoplasmosis". BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 321 (7254): 142–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7254.142. PMC 27431. PMID 10894691.

- Jump up ^ Bobić B, Jevremović I, Marinković J, Sibalić D, Djurković-Djaković O (September 1998). "Risk factors for Toxoplasma infection in a reproductive age female population in the area of Belgrade, Yugoslavia". European journal of epidemiology 14 (6): 605–10. doi:10.1023/A:1007461225944. PMID 9794128.

- Jump up ^ Jones JL, Dargelas V, Roberts J, Press C, Remington JS, Montoya JG (2009). "Risk Factors forToxoplasma gondiiInfection in the United States". Clinical Infectious Diseases 49 (6): 878–884. doi:10.1086/605433. PMID 19663709.

- Jump up ^ Circular Normativa sobre Cuidados Pré-Concepcionais – Direcção-Geral de Saúde

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sukthana Y (March 2006). "Toxoplasmosis: beyond animals to humans". Trends Parasitol. 22 (3): 137–42. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2006.01.007. PMID 16446116.

- Jump up ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b De Paschale M, Agrappi C, Clerici P, Mirri P, Manco MT, Cavallari S, Viganò EF (2008). "Seroprevalence and incidence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in the Legnano area of Italy". Clinical Microbiology and Infection : the Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 14 (2): 186–9. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01883.x. PMID 18034857.

- Jump up ^ Kanková S, Sulc J, Nouzová K, Fajfrlík K, Frynta D, Flegr J (2007). "Women infected with parasite Toxoplasma have more sons". Die Naturwissenschaften 94 (2): 122–7. doi:10.1007/s00114-006-0166-2. PMID 17028886.

- Jump up ^ Ian Sample, science correspondent (2006-10-12). "Pregnant women infected by cat parasite more likely to give birth to boys, say researchers | Science". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Dalimi A, Abdoli A (2011). "Latent Toxoplasmosis and Human". Iranian Journal of Parasitology 7 (1): 1–17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Webster JP, McConkey GA (June 2010). "Toxoplasma gondii-altered host behaviour: clues as to mechanism of action". Folia parasitologica 57 (2): 95–104. doi:10.14411/fp.2010.012. PMID 20608471.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Webster JP (May 2007). "The effect of Toxoplasma gondii on animal behavior: playing cat and mouse". Schizophrenia bulletin 33 (3): 752–6. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl073. PMC 2526137. PMID 17218613.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berdoy M, Webster JP, Macdonald DW (Aug 7, 2000). "Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii". Proceedings. Biological sciences / the Royal Society 267 (1452): 1591–4. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1182. PMC 1690701. PMID 11007336.

- Jump up ^ Vyas A, Kim SK, Giacomini N, Boothroyd JC, Sapolsky RM (Apr 10, 2007). "Behavioral changes induced by Toxoplasma infection of rodents are highly specific to aversion of cat odors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (15): 6442–7. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.6442V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608310104. PMC 1851063. PMID 17404235.

- Jump up ^ Xiao J, Kannan G, Jones-Brando L, Brannock C, Krasnova IN, Cadet JL, Pletnikov M, Yolken RH (Mar 29, 2012). "Sex-specific changes in gene expression and behavior induced by chronic Toxoplasma infection in mice". Neuroscience 206: 39–48. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.12.051. PMID 22240252.

- Jump up ^ Lamberton PH, Donnelly CA, Webster JP (September 2008). "Specificity of theToxoplasma gondii-altered behaviour to definitive versus non-definitive host predation risk". Parasitology 135 (10): 1143–50. doi:10.1017/S0031182008004666. PMID 18620624.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hari Dass SA, Vyas A (December 2014). "Toxoplasma gondii infection reduces predator aversion in rats through epigenetic modulation in the host medial amygdala". Mol. Ecol. 23 (24): 6114–6122. doi:10.1111/mec.12888. PMID 25142402.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Flegr J, Markoš A (December 2014). "Masterpiece of epigenetic engineering - how Toxoplasma gondii reprogrammes host brains to change fear to sexual attraction". Mol. Ecol. 23 (24): 5934–5936. doi:10.1111/mec.13006. PMID 25532868.

- Jump up ^ McCowan TJ, Dhasarathy A, Carvelli L (February 2015). "The Epigenetic Mechanisms of Amphetamine" (PDF). J. Addict. Prev. (Avens Publishing Group) (S1): 1–7. ISSN 2330-2178. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

Epigenetic modifications caused by addictive drugs play an important role in neuronal plasticity and in drug-induced behavioral responses. Although few studies have investigated the effects of AMPH on gene regulation (Table 1), current data suggest that AMPH acts at multiple levels to alter histone/DNA interaction and to recruit transcription factors which ultimately cause repression of some genes and activation of other genes. Importantly, some studies have also correlated the epigenetic regulation induced by AMPH with the behavioral outcomes caused by this drug, suggesting therefore that epigenetics remodeling underlies the behavioral changes induced by AMPH. If this proves to be true, the use of specific drugs that inhibit histone acetylation, methylation or DNA methylation might be an important therapeutic alternative to prevent and/or reverse AMPH addiction and mitigate the side effects generate by AMPH when used to treat ADHD.

- Jump up ^ Walker DM, Cates HM, Heller EA, Nestler EJ (February 2015). "Regulation of chromatin states by drugs of abuse". Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 30: 112–121. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2014.11.002. PMID 25486626.

- Jump up ^ Nestler EJ (January 2014). "Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction". Neuropharmacology. 76 Pt B: 259–268. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.004. PMC 3766384. PMID 23643695.

Short-term increases in histone acetylation generally promote behavioral responses to the drugs, while sustained increases oppose cocaine’s effects, based on the actions of systemic or intra-NAc administration of HDAC inhibitors. ... Genetic or pharmacological blockade of G9a in the NAc potentiates behavioral responses to cocaine and opiates, whereas increasing G9a function exerts the opposite effect (Maze et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2012a). Such drug-induced downregulation of G9a and H3K9me2 also sensitizes animals to the deleterious effects of subsequent chronic stress (Covington et al., 2011). Downregulation of G9a increases the dendritic arborization of NAc neurons, and is associated with increased expression of numerous proteins implicated in synaptic function, which directly connects altered G9a/H3K9me2 in the synaptic plasticity associated with addiction (Maze et al., 2010).

G9a appears to be a critical control point for epigenetic regulation in NAc, as we know it functions in two negative feedback loops. It opposes the induction of ΔFosB, a long-lasting transcription factor important for drug addiction (Robison and Nestler, 2011), while ΔFosB in turn suppresses G9a expression (Maze et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2012a). ... Also, G9a is induced in NAc upon prolonged HDAC inhibition, which explains the paradoxical attenuation of cocaine’s behavioral effects seen under these conditions, as noted above (Kennedy et al., 2013). GABAA receptor subunit genes are among those that are controlled by this feedback loop. Thus, chronic cocaine, or prolonged HDAC inhibition, induces several GABAA receptor subunits in NAc, which is associated with increased frequency of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs). In striking contrast, combined exposure to cocaine and HDAC inhibition, which triggers the induction of G9a and increased global levels of H3K9me2, leads to blockade of GABAA receptor and IPSC regulation. - Jump up ^ Vanagas L, Jeffers V, Bogado SS, Dalmasso MC, Sullivan WJ, Angel SO (October 2012). "Toxoplasma histone acetylation remodelers as novel drug targets". Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 10 (10): 1189–1201. doi:10.1586/eri.12.100. PMC 3581047. PMID 23199404.

- Jump up ^ Bouchut A, Chawla AR, Jeffers V, Hudmon A, Sullivan WJ (2015). "Proteome-wide lysine acetylation in cortical astrocytes and alterations that occur during infection with brain parasite Toxoplasma gondii". PLoS ONE 10 (3): e0117966. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117966. PMC 4364782. PMID 25786129.

- Jump up ^ McConkey GA, Martin HL, Bristow GC, Webster JP (Jan 1, 2013). "Toxoplasma gondii infection and behaviour – location, location, location?". The Journal of experimental biology 216 (Pt 1): 113–9. doi:10.1242/jeb.074153. PMC 3515035. PMID 23225873.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Afonso C, Paixão VB, Costa RM (2012). Hakimi, ed. "Chronic Toxoplasma infection modifies the structure and the risk of host behavior". PLoS ONE 7 (3): e32489. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732489A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032489. PMC 3303785. PMID 22431975.

- Jump up ^ Gonzalez LE, Rojnik B, Urrea F, Urdaneta H, Petrosino P, Colasante C, Pino S, Hernandez L (Feb 12, 2007). "Toxoplasma gondii infection lower anxiety as measured in the plus-maze and social interaction tests in rats A behavioral analysis". Behavioural Brain Research 177 (1): 70–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2006.11.012. PMID 17169442.

- Jump up ^ Ho-Yen DO, Joss AW, Balfour AH, Smyth ET, Baird D, Chatterton JM (October 1992). "Use of the polymerase chain reaction to detect Toxoplasma gondii in human blood samples". J. Clin. Pathol. 45 (10): 910–3. doi:10.1136/jcp.45.10.910. PMC 495065. PMID 1430262.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Montoya JG (2002). "Laboratory diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii infection and toxoplasmosis". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 185 Suppl 1: S73–82. doi:10.1086/338827. PMID 11865443.

- Jump up ^ Montoya, Jose. "Laboratory diagnosis of toxoplama gondii infection and toxoplasmosis". The journal of infectious diseases 185: s73–s82. doi:10.1086/338827. PMID 11865443.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Lin MH, Chen TC, Kuo TT, Tseng CC, Tseng CP (2000). "Real-time PCR for quantitative detection of Toxoplasma gondii". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 38 (11): 4121–5. PMC 87551. PMID 11060078.

- Jump up ^ Doggett JS, Nilsen A, Forquer I, Wegmann KW, Jones-Brando L, Yolken RH, Bordón C, Charman SA, Katneni K, Schultz T, Burrows JN, Hinrichs DJ, Meunier B, Carruthers VB, Riscoe MK (2012). "Endochin-like quinolones are highly efficacious against acute and latent experimental toxoplasmosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (39): 15936–41. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208069109. PMC 3465437. PMID 23019377.

- Jump up ^ [dead link]"Toxoplasmosis – treatment key research". NAM & aidsmap. 2005-11-02.

- Jump up ^ Djurković-Djaković O, Milenković V, Nikolić A, Bobić B, Grujić J (2002). "Efficacy of atovaquone combined with clindamycin against murine infection with a cystogenic (Me49) strain of Toxoplasma gondii" (PDF). J Antimicrob Chemother 50 (6): 981–7. doi:10.1093/jac/dkf251. PMID 12461021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pappas G, Roussos N, Falagas ME (October 2009). "Toxoplasmosis snapshots: global status of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence and implications for pregnancy and congenital toxoplasmosis". International Journal for Parasitology 39 (12): 1385–94. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.04.003. PMID 19433092.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jones JL, Kruszon-Moran D, Sanders-Lewis K, Wilson M (September 2007). "Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States, 1999 2004, decline from the prior decade". The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 77 (3): 405–10. PMID 17827351.

- Jump up ^ Sibley LD; Khan A; Ajioka JW; Rosenthal BM (2009). "Genetic diversity of Toxoplasma gondii in animals and humans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1530): 2749–2761. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0087. PMID 19687043.

- Jump up ^ "CDC: Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection) – Pregnant Women". Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- Jump up ^ Dubey JP, Frenkel JK (May 1998). "Toxoplasmosis of rats: a review, with considerations of their value as an animal model and their possible role in epidemiology". Veterinary parasitology 77 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(97)00227-6. PMID 9652380.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Ferguson DJ (2009). "Toxoplasma gondii: 1908-2008, homage to Nicolle, Manceaux and Splendore". Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 104 (2): 133–48. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762009000200003. PMID 19430635.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Weiss LM, Dubey JP (2009). "Toxoplasmosis: A history of clinical observations". International Journal for Parasitology 39 (8): 895–901. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.02.004. PMC 2704023. PMID 19217908.

- Jump up ^ Toxoplasma Serology Laboratory: Laboratory Tests For The Diagnosis Of Toxoplasmosis

- Jump up ^ "How Your Cat Is Making You Crazy - Kathleen McAuliffe". The Atlantic. 2012-02-06. Retrieved 2013-06-03.

- Jump up ^ "'Cat Lady' Conundrum - Rebecca Skloot". The New York Times. 2007-12-09.

- Jump up ^ "Your cat is making you crazy, says scientist - Lorianna De Giorgio". Toronto Star. 2012-02-18.

- Jump up ^ "Why Your Cat May Be Making You Crazy". Animal Planet. 2012-03-01.

- Jump up ^ Fox, Stuart (2010-03-09). "Gold Nanoparticles and Lasers Kill the Brain Parasite That Causes "Crazy Cat Lady" Syndrome". Popsci.

- Jump up ^ Kapperud, Georg; Jenum, Pal A.; Stray-Pedersen, Babill; Melby, Kjetil K.; Eskild, Anne; Eng, Jan (1996-08-15). "Risk Factors for Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Pregnancy Results of a Prospective Case-Control Study in Norway". American Journal of Epidemiology 144 (4): 405–412. ISSN 0002-9262. PMID 8712198.

- Jump up ^ Cook, A. J. C.; Holliman, Richard; Gilbert, R. E.; Buffolano, W.; Zufferey, J.; Petersen, E.; Jenum, P. A.; Foulon, W.; Semprini, A. E. (2000-07-15). "Sources of toxoplasma infection in pregnant women: European multicentre case-control studyCommentary: Congenital toxoplasmosis—further thought for food". BMJ 321 (7254): 142–147. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7254.142. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 10894691.

- Jump up ^ Torrey, E.; Simmons, Wendy; Yolken, Robert (June 2015). "Is childhood cat ownership a risk factor for schizophrenia later in life?". Schizophrenia Research, Volume 165, Issue 1. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2015.03.036.

- Jump up ^ Kathleen McAuliffe (March 2012). "How Your Cat is Making You Crazy". The Atlantic.

- Jump up ^ Jaroslav Flegr: Effects of Toxoplasma on Human Behavior Schizophrenia Bulletin, Volume 33 Issue 3, Pp. 757-760

- Jump up ^ Arthur Ashe, Tennis Star, is Dead at 49 New York Times (02/08/93)

- Jump up ^ Merritt Butrick, A Biography Angelfire.com, accessdate Mar 18, 2011

- Jump up ^ "Pregnancy superfoods revealed". BBC News. January 10, 2001. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- Jump up ^ "Olympics bid Coes finest race". The Times (London). June 26, 2005. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- Jump up ^ Brody, Jane E. (27 October 1982). "PERSONAL HEALTH". New York Times.

- Jump up ^ "Topic 33. Coccidia and Cryptosporidium spp". Biology 625: Animal Parasitology. Kent State Parasitology Lab. October 24, 2005. Retrieved 2006-10-01. Includes a list of famous victims.

- Jump up ^ http://www.101greatgoals.com/blog/the-infinite-appeal-of-the-wealdstone-raider-feature/

- Jump up ^ Higson, Charlie (2014). The Fallen (U.S. ed.). Hyperion. pp. Chapter 70, pages 374–381. ISBN 978-1423165668.

- Jump up ^ Higson, Charlie (2014). The Fallen (U.S. ed.). Hyperion. p. Chapter 66, pages 360. ISBN 978-1423165668.

- Jump up ^ Higson, Charlie (2014). The Fallen (U.S. ed.). Hyperion. p. 370. ISBN 978-1423165668.

- Jump up ^ Higson, Charlie (2014). The Fallen (U.S. ed.). Hyperion. p. 362. ISBN 978-1423165668.

- Jump up ^ Higson, Charlie (2014). The Fallen (U.S. ed.). Hyperion. ISBN 978-1423165668. Most recently described in Chapter 70.

- Jump up ^ Higson, Charlie (2010). The Dead. Puffin. ISBN 978-1423134121.

- Jump up ^ Higson, Charlie (2014). The Fallen (U.S. ed.). Hyperion. ISBN 978-1423165668.

- Jump up ^ Rigoulet, Jacques; Hennache, Alain; Lagourette, Pierre; George, Catherine; Longeart, Loïc; Le Net, Jean-Loïc; Dubey, Jitender P. (2014). "Toxoplasmosis in a bar-shouldered dove (Geopelia humeralis) from the Zoo of Clères, France". Parasite 21: 62. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014062. ISSN 1776-1042. PMID 25407506.

- Jump up ^ J.P Dubey (2010)

- Jump up ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15357087

- Jump up ^ Chessa G, Chisu V, Porcu R, Masala G (2014). "Molecular characterization of Toxoplasma gondii Type II in sheep abortion in Sardinia, Italy". Parasite 21: 6. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014007. PMC 3927306. PMID 24534616.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Tenter AM, Heckeroth AR, Weiss LM (November 2000). "Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans". International Journal for Parasitology 30 (12–13): 1217–58. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00124-7. PMC 3109627. PMID 11113252.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Jones JL, Dubey JP (September 2012). "Foodborne toxoplasmosis". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 55 (6): 845–51. doi:10.1093/cid/cis508. PMID 22618566.

- Jump up ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 145-151

- Jump up ^ Dubey JP, Sundar N, Hill D, Velmurugan GV, Bandini LA, Kwok OC, Majumdar D, Su C (July 2008). "High prevalence and abundant atypical genotypes of Toxoplasma gondii isolated from lambs destined for human consumption in the USA". International Journal for Parasitology 38 (8–9): 999–1006. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.11.012. PMID 18191859.

- Jump up ^ Dubey JP, Rajendran C, Ferreira LR, Martins J, Kwok OC, Hill DE, Villena I, Zhou H, Su C, Jones JL (July 2011). "High prevalence and genotypes ofToxoplasma gondii isolated from goats, from a retail meat store, destined for human consumption in the USA". International Journal for Parasitology 41 (8): 827–33. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.03.006. PMID 21515278.

- Jump up ^ Dubey JP (February 2010). "Toxoplasma gondii infections in chickens (Gallus domesticus): prevalence, clinical disease, diagnosis and public health significance". Zoonoses and public health 57 (1): 60–73. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01274.x. PMID 19744305.

- Jump up ^ Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 723

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Elmore SA, Jones JL, Conrad PA, Patton S, Lindsay DS, Dubey JP (April 2010). "Toxoplasma gondii: epidemiology, feline clinical aspects, and prevention". Trends in parasitology 26 (4): 190–6. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2010.01.009. PMID 20202907.

- Jump up ^ Jokelainen P, Simola O, Rantanen E, Näreaho A, Lohi H, Sukura A (November 2012). "Feline toxoplasmosis in Finland: cross-sectional epidemiological study and case series study". Journal of veterinary diagnostic investigation : official publication of the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians, Inc 24 (6): 1115–24. doi:10.1177/1040638712461787. PMID 23012380.

- Jump up ^ Al-Kappany YM, Rajendran C, Ferreira LR, Kwok OC, Abu-Elwafa SA, Hilali M, Dubey JP (December 2010). "High prevalence of toxoplasmosis in cats from Egypt: isolation of viable Toxoplasma gondii, tissue distribution, and isolate designation". The Journal of parasitology 96 (6): 1115–8. doi:10.1645/GE-2554.1. PMID 21158619.

- Jump up ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 95

- Jump up ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 46

- Jump up ^ Conrad PA, Miller MA, Kreuder C, James ER, Mazet J, Dabritz H, Jessup DA, Gulland F, Grigg ME (2005). "Transmission of Toxoplasma: clues from the study of sea otters as sentinels of Toxoplasma gondii flow into the marine environment". Int J Parasitol 35 (11–12): 1155–68. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.002. PMID 16157341.

- Jump up ^ 17:30–22:00 "Treating Disease in the Developing World". Talk of the Nation Science Friday. National Public Radio. December 16, 2005.

- Jump up ^ "Parasite in cats killing sea otters". NOAA magazine (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 21 January 2003. Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- Jump up ^ 3 Schizophrenia

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Webster JP, Kaushik M, Bristow GC, McConkey GA (Jan 1, 2013). "Toxoplasma gondii infection, from predation to schizophrenia: can animal behaviour help us understand human behaviour?". The Journal of experimental biology 216 (Pt 1): 99–112. doi:10.1242/jeb.074716. PMC 3515034. PMID 23225872.

- Jump up ^ Pearce BD, Kruszon-Moran D, Jones JL (Aug 15, 2012). "The relationship between Toxoplasma gondii infection and mood disorders in the third National Health and Nutrition Survey". Biological Psychiatry 72 (4): 290–5. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.003. PMID 22325983.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Torrey EF, Yolken RH (May 2007). "Schizophrenia and toxoplasmosis". Schizophrenia bulletin 33 (3): 727–8. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm026. PMC 2526129. PMID 17426051.

- Jump up ^ Fanous AH, Kendler KS (2005). "Genetic heterogeneity, modifier genes, and quantitative phenotypes in psychiatric illness: searching for a framework". Molecular psychiatry 10: 6–13. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001571.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Torrey EF, Bartko JJ, Yolken RH (2012). "Toxoplasmosis gondii and other risk factors for Schizophrenia: An Update". Schizophrenia Bulletin 38: 642–647. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbs043.

- Jump up ^ Niebuhr DW, Millikan AM, Cowan DN, Yolken R, Li Y, Weber NS (2005). "Selected infectious agents and risk of schizophrenia among U.S. military personnel". American journal of psychiatry 165: 99–106. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06081254.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Horacek J, Flegr J, Tintera J, Verebova K, Spaniel F, Novak T, Brunovsky M, Bubenikova-Valesova V, Holub D, Palenicek T, Hoschl C (2012). "Latent toxoplasmosis reduces grey matter density in schizophrenia but not in controls:Voxel-based-morphometry (VBM) study". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 13: 501–509. doi:10.3109/15622975.2011.573809.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holub D, Flegr J, Dragomirecka E, Rodriguez M, Preiss M, Novak T, Cermak J, Horacek J, Kodym P, Libiger J, Hoschl C, Motlova LB (2013). "Difference in onset of disease and severity of psychopathology between toxoplasmosis-related and toxoplasmosis-unrelated schizophrenia". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 127: 227–238. doi:10.1111/acps.12031.

- Jump up ^ Kodym P, Maly M, Svandova E, Lezatkova H, Bazoutova M, Vlckova J, Benes C, Zastera M (2001). "Toxoplasma n the Czech Republic 1923-1999: first case to widespread outbreak". Int. J. Parasitol. 31: 125–132.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Flegr J (2013). "How and why toxoplasma makes us crazy". Trend in Parasitology 29: 156–163. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2013.01.007.

- Jump up ^ Keller WR, Kum LM, Wehring HJ, Koola MM, Buchanan RW, Kelly DL (Apr 2013). "A review of anti-inflammatory agents for symptoms of schizophrenia.". Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 27 (4): 337–42. doi:10.1177/0269881112467089. PMID 23151612.

- Jump up ^ Gaskell EA, Smith JE, Pinney JW, Westhead DR, McConkey GA (Mar 2009). "A unique dual activity amino acid hydroxylase in Toxoplasma gondii". PLoS ONE 4 (3): e4801. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004801.

- Jump up ^ Science Daily:Toxoplasmosis Parasite May Trigger Schizophrenia And Bipolar Disorders. March 11, 2009

- Jump up ^ Prandovsky, E; Gaskel, E; Martin, H; Dubey, JP; Webster, JP; McConkey, GA (September 2011). "The Neurotropic Parasite Toxoplasma Gondii Increases Dopamine Metabolism". PLoS ONE 6 (9): e23866. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023866.

- Jump up ^ Silva, NM; Rodrigues, CV; Santoro, MM; Reis, LF; Varez-Leite, JI; Gazzinelli, RT (2002). "Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, tryptophan degradation, and kynurenine formation during in vivo infection with Toxoplasma gondii : induction by endogenous gamma interferon and requirement of interferon regulatory factor 1". Infection and Immunity 70: 859–869. doi:10.1128/IAI.70.2.859-868.2002.

- Jump up ^ Notarangelo, FM; Wilson, EH; Horning, KJ; Thomas, MAR; Harris, TH; Fang, Q (2014). "Evaluation of kynurenine pathway metabolism in Toxoplasma gondii-infected mice: Implications for schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research 152: 261–267. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.11.011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Flegr J (Jan 1, 2013). "Influence of latent Toxoplasma infection on human personality, physiology and morphology: pros and cons of the Toxoplasma-human model in studying the manipulation hypothesis". The Journal of experimental biology 216 (Pt 1): 127–33. doi:10.1242/jeb.073635. PMID 23225875.

- Parts of this article are taken from the public domain CDC factsheet: Toxoplasmosis

Bibliography[edit]

- Louis M Weiss; Kami Kim (28 April 2011). Toxoplasma Gondii: The Model Apicomplexan. Perspectives and Methods. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-047501-1. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- J. P. Dubey (15 April 2010). Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-9237-0. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Speer CA (April 1998). "Structures of Toxoplasma gondii Tachyzoites, Bradyzoites, and Sporozoites and Biology and Development of Tissue Cysts". Clinical Microbiology Reviews 11 (2): 267–299. PMC 106833. PMID 9564564.

- Jaroslav Flegr (2011). Pozor, Toxo!. Academia, Prague, Czech republic. ISBN 978-80-200-2022-2. Retrieved 2011.

External links[edit]

- How a cat-borne parasite infects humans (National Geographic)

- Toxoplasmosis at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- Toxoplasmosis at Health Protection Agency (HPA), United Kingdom

- Pictures of Toxoplasmosis Medical Image Database

- Video-Interview with Professor Robert Sapolsky on Toxoplasmosis and its effect on human behavior (24:27 min)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

No comments:

Post a Comment